Table of Contents

Ikebana, rooted in Buddhist flower offerings and Japan’s ancient view of nature, began to take form as an artistic expression during the Muromachi period. Though politically unstable, this era saw the rise of austere and spiritually focused aesthetics, strongly influenced by Zen Buddhism.

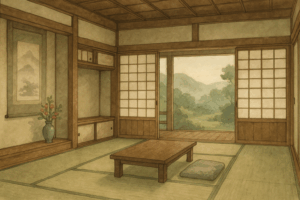

The Birth of Shoin-zukuri and the Tokonoma

During the Muromachi period, a new architectural style called Shoin-zukuri was adopted in the residences of the warrior class. This led to the creation of the tokonoma—an alcove for displaying flowers and hanging scrolls. As a result, the act of displaying flowers became an integral part of interior decor and cultural life.

The Establishment of Rikka and Ikenobō Senkei

During this period, Ikenobō Senkei, a monk of Rokkakudō Temple in Kyoto, developed a floral style that went beyond religious offerings. He introduced a form called Rikka (standing flowers), emphasizing structural beauty and symbolism. This style featured a tall central branch representing heaven, and was balanced with branches expressing earth and humanity, reflecting the cosmic order. Materials like pine, willow, and wildflowers were used to represent the natural landscape and universal harmony within a single arrangement.

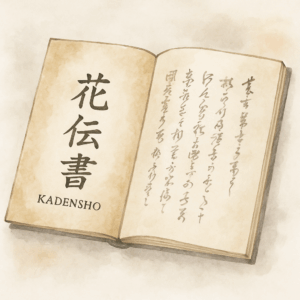

Systematization as an Art Form

Rikka was embraced by the samurai class as a practice for spiritual cultivation and refinement. The emergence of written texts known as Kadensho (flower treatises) helped to formalize theories and aesthetics of flower arrangement. Through this, ikebana evolved into an art form grounded in structure and philosophy.

Influence from Foreign Cultures

During the Muromachi period, Japan engaged in tribute trade with the Ming dynasty in China, resulting in cultural exchanges. The influence of Zen Buddhism from China introduced artistic values centered on stillness, emptiness, and nothingness. However, ikebana did not develop through direct importation of foreign techniques. Instead, it grew primarily from Japan’s indigenous sensibility toward flowers.

Connection with Common People

In this period, ikebana was mainly practiced within temples, samurai households, and aristocratic circles. The general public only began to enjoy ikebana more freely in the Edo period. That said, toward the end of the Muromachi period, the spread of tea culture (chanoyu) may have contributed to the gradual diffusion of floral decoration into merchant and urban communities.

Conclusion

The Muromachi period marked a major shift in ikebana from a spiritual offering to an art form with structural principles. The development of the Rikka style by Ikenobō Senkei and the appearance of Kadensho laid the foundation for modern ikebana. In the next article, we will explore how ikebana diversified into different schools and spread among the common people during the Edo period.